Vogue CS in English

Zuzana Čaputová in an exclusive interview with Madeleine Albright

Vogue Leaders14. 6. 2021

Zuzana Čaputová, the first woman to become President of Slovakia, and Madeleine Albright, the first woman to become United States Secretary of State. Two women with exceptional and completely unpredictable careers. Two top-tier politicians, successful in a field that is (and likely will continue to be) dominated by men. Two important public figures who know of each other, cheer each other on, but have never had the chance to meet. Perhaps because of this, both accepted Czechoslovak Vogue’s invitation to take part in an exclusive double interview on leadership, Václav Havel and freedom. The questions were asked by Emma Smetana, directly from the maternity ward where she gave birth to her second daughter the day before, and Michaela Dombrovská.

The online interview was conducted in Czech and Slovak.

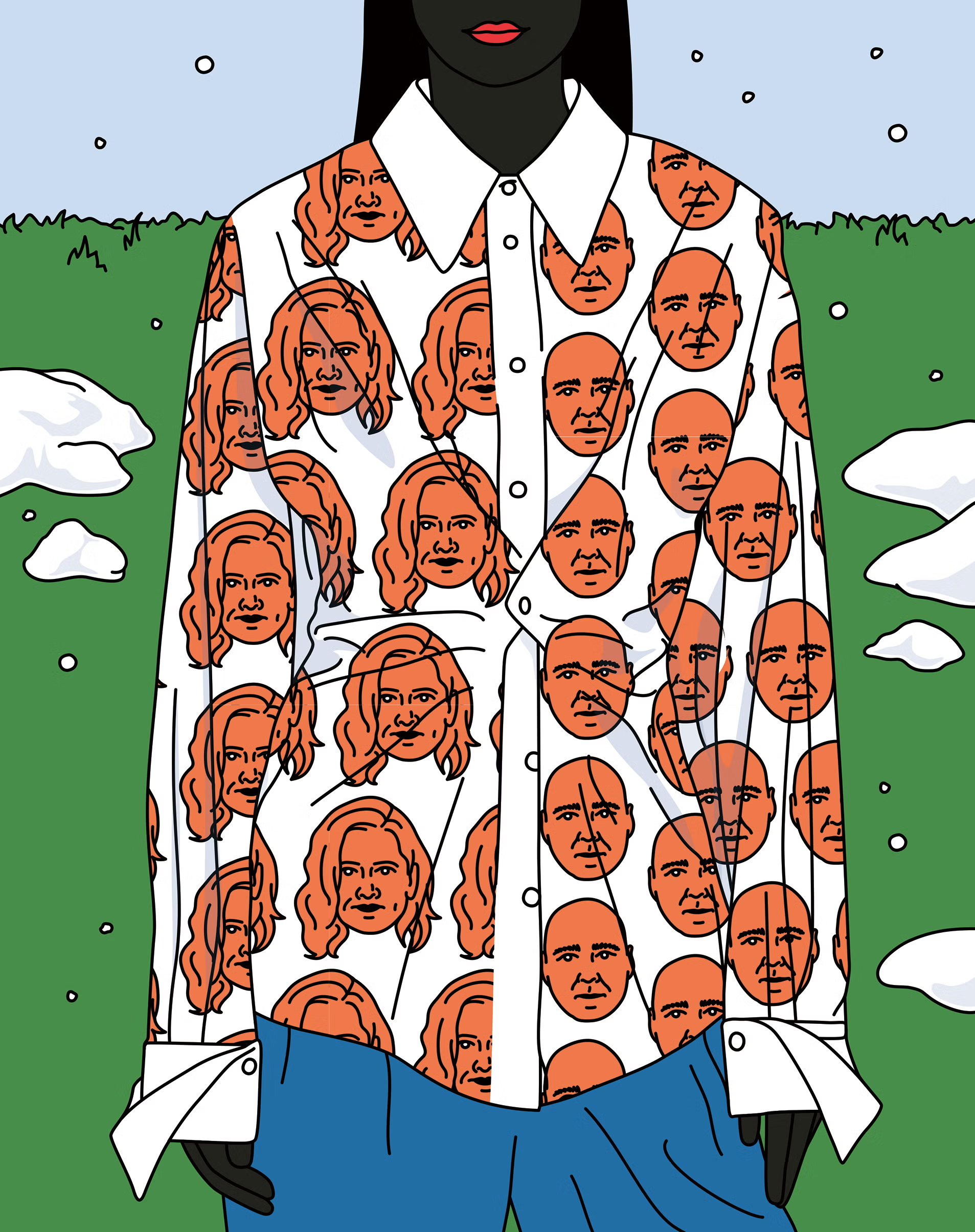

Foto: Branislav Šimončík

ES: I’m delighted that I can conduct our virtual meeting despite the unexpected turn of events. And with your permission, I will not begin in the usual way. Instead, I’d like to ask you something personal. Both of you have daughters [editor’s note: Zuzana Čaputová has two, Madeleine Albright three] and as of yesterday I do, too. In your experience, is there something unique about the lot of a mother with two or more girls?

MA: My two older daughters are twins, so I didn’t have time to think about their number. But it’s wonderful and a great joy. My third child is also a girl. And then I have six grandchildren, four of whom are boys. And it’s true that it’s different when there are boys around.

ZČ: For me it’s also a wonderful experience and I’m grateful for it. I have to say that as far back as I can remember, my daughters have always been my friends. The relationship has always been very open, I’d even say partner-like, to the point where I sometimes have to remind them that I’m also their mom. It’s certainly different than having sons. Whenever I see families with boys, I realize the differences. Fate has given me two daughters and I’m happy for that. And I wish you all the best, Emma – it’s a wonderful thing. Congratulations on the baby, and I wish you both good health.

ES: Thank you very much! What kind of women did you want to raise your daughters to be?

MA: I mainly wanted to raise daughters that would understand they also have to do things for others. To really think about what they’d like to achieve in this world. My daughters are older than you – the twins are almost sixty, the youngest fifty-four. I sometimes lie about how old they are because it shows how old I am. (laughter). And all of them are doing what I thought they should be. One twin is a judge, and the second works for Global Partnership for Education (GPE). The third is helping abused children. I’d always really hoped they would realize what they had and give something back to society.

ZČ: In my case I have no plans for how I’d like to raise them in terms of their role in society or their profession. It’s very important for me that they grow up – and both are almost adults – into compassionate and empathetic human beings. What’s most important is that they choose their own path to personal fulfilment themselves. That they be true to themselves and happy in what they do. That they do what they enjoy. They’ve successfully chosen a completely different path than me – neither wants to be a lawyer or a politician – at least for now that is. That’s good I think. They’re choosing their own path in life.

MD: You daughters are on the threshold of their professional careers. In terms of opportunity, what kind of world are they entering?

ZČ: I believe things are changing for the better, even in Slovakia. In terms of both career opportunities for women and the position of women in society. Of course, we still have a long way to go before we achieve equality or equal opportunity for women. I do believe, however, that my daughters will gradually be entering a professional world that will, I hope, be fairer to women. I believe they will be able to enter it confidently, unburdened by the preconception that as women they cannot pursue their goals. The fact that people put their trust in me and elected me the first woman to head the country will, I believe, also help change the atmosphere.

ES: Mrs. Albright, more than twenty years ago you took one of the most important offices in the world and became the US Secretary of State. Since then, have you seen a substantial shift in terms of the representation of women in top posts? And how much has the level of support given to women by husbands, colleagues or partners changed?

Foto: Vogue CS

MA: Things have truly become easier. Today it’s normal for women to hold high offices and are partners with men. In the USA, we believe we have to have been the first in everything. But we have never had a woman for president. In the Eighties, we tried to elect the first female vice president. That didn’t happen though. Until now. Kamala Harris. And it’s wonderful. I know her well and believe she will leave behind a good piece of work. When I was Secretary of State, some people said that a woman was wrong for this post because the leaders of Arab countries wouldn’t work with her. But there were no problems there. I had more problems with people in our own government because they weren’t used to it. They were wondering why they didn’t get the position, why it was given to some woman. I think the situation is better today, even though we in the USA are a little slow. Slovakia has surpassed us! We cannot, however, think it’s over, that it can’t all be reversed. There are conservatives everywhere, even in America, who think a woman’s place is in the home, to cook and have children. We have to be vigilant. And women have to support other women – that’s what I consider to be the most important.

ES: In other words, you’re saying that there are many men – and maybe even women – who are just starting to adapt to a changing reality. Do you think it has to do with how they were raised?

MA: Boys have to be raised to see that partnership is the best. People sometimes ask me if the world wouldn’t be better if only women held high positions. I always tell them that if they believe that, then they need to think back to high school where it was the girls who were in charge. It’s better when women and men work together. The way we work and think is a little different. I don’t want to generalize, but men are sometimes better at working on one problem in depth and women on more things at once. It’s better when women and men work together.

ZČ: The more men are exposed to seeing women active in, say, politics or the public realm, the more this experience can shift perspectives. Perhaps more so than just being told so by their mothers, although this is important as well. Just as a teacher plays a vital role in raising children in a school environment, a mother and how she manages her role with respect to her sons is also very important – in terms of the model that a mother represents in the family. I therefore think developments in this area – and I see they are tending towards improvement – are not fixed or on a one-way street. I completely agree with that. Things can start moving completely in the opposite direction at any time. In this regard, the role of women in making room for other women continues to be very important.

ES: Now an obligatory question, seeing as we have arranged this meeting on the occasion of the publication of the first issue of Vogue Leaders: Are the traits that a true leader should possess different for a woman than for a man?

ZČ: As regards what traits make a good leader and the difference between women and men, I think women and men differ already in terms of their life experience. In this sense, I believe that women leaders possess different traits than their male counterparts. I completely agree with Mrs. Albright that our representation in leadership should be in the same proportion as our representation in the general population. One-sidedness would lead to an imbalance.

MA: Leadership is when people, whether women or men, listen to others. To truly be able to listen and not just talk. It’s important to have people around you who will not always agree with you. To give people a real chance to say what they think and to respect their opinions. Not to think that a leader knows everything and does not need other people around. Leadership is having a team and taking action together. It’s also the ability to put yourself in the shoes of the other side and figure out what they need. It’s not always about winning, but about actually doing something. To get a good result. Winning is not always the most important thing.

ZČ: I’d just like to add to what Mrs. Albright said. I read a quote a long time ago that I’d like to paraphrase, as it is perhaps indicative of what makes a good leader. “Take sole responsibility for your failures, but share your successes.” What I like about this quote is its reference to the courage of a leader to take responsibility, to take risk, but then, if successful, to show humility, humbleness, team spirit. It’s a very old message but at the same time very current in my opinion.

MD: Madam President, do you feel a certain responsibility for forging a path for woman and inspiring them?

ZČ: It’s an integral part of my role. It’s also about the fact that I’m a woman and the first female president and that there are few female presidents in the world despite it being so big. So yes, it’s a part of the responsibility of my office. I know that it’s a very important, personal thing for young women and girls, and something they often express in letters, drawings and messages. Young girls in particular imagine themselves in such a role. I also believe it can also be an inspiration to other women who are thinking about entering politics.

ES: What do you, Zuzana Čaputová, admire about Madeleine Albright? And what do you, Madeleine Albright, admire about Zuzana Čaputová?

ZČ: It’s hard for me to summarize it in a single sentence, but I’ll try, although it won’t be an all-encompassing answer. I think that at the time that you were politically active you were a pioneer for women in high politics. What I know about your time in politics is that it also required a big dose of courage. I would emphasize the courage and put it in first place. It of course required a lot of other skills and attributes, but it is the courage I wanted to underscore.

MA: Thank you very much. What I really admire about you when I look at what’s going on in Slovakia is the way you work. That you really listen to what’s going on. That you’re able to work and do something for your people despite the complicated political situation. Not only think about who will win, but also doing what you were elected to do. Your country can be proud of what you’re doing and how you’re working in light of the complicated situations in other countries, faced by your neighbors.

ZČ: Thank you.

MD: Mrs. Albright, if you image the world twenty years from now, what could or should it be like in terms of leadership and the involvement of women in leadership roles?

MA: I hope that we’ll understand what’s going on right now. What’s going on with technology and information. That we’ll understand how new technologies are changing the world. How countries will communicate and cooperate with one another. I hope we’re not going to keep acting nationalistically and comparing who is better. And I hope that we will be cooperating globally. I also hope that we won’t keep having to talk about who’s better, women or men. That we will be working together to find solutions to the problems we’re facing. It’s really important to see a chance, to be optimistic. Especially when it comes to youth, who are learning in a completely different way. Teaching at university, I can see that the students know how to do a lot more than I once could.

ZČ: Let me add to that. What kind of world would I like to see in thirty years? I’d be happy if there was greater respect for the principle of balance. Whether it be opportunities for women or respect for nature, especially in connection with climate change. This is very closely related to the deepest human traits, and this leads me to something I consider to be very important but neglected: self-development, self-cultivation. And a return to basic values is a part of this. Our working on our growth or how we mature also lays the foundation for relationships, including between nations and countries, to prosper.

MD: Mrs. Albright, you have said several times that the countries that have been best at handling the current pandemic are countries that are governed by women. And that female leadership has showed its strength at this time. What is that strength?

MA: It’s really interesting what’s going on. Women think about how to help people and not who’s the most important or who has money. They really think about what’s happing to all of society. They of course understand that sometimes it’s important to know how to ask for help. That it’s not a sign of weakness. Those women who are handling the crisis successfully are not thinking just about themselves – they are not egoists. They work for their fellow citizens.

MD: Madam President, you are one of those women in the center of events. Do you feel that you’re acting differently that a man would in your position?

ZČ: Of course. The way I’m performing my presidential role, the way I communicate, has a lot to do with the fact that I’m a woman. At the same time, I’d like to add that I’m a president without executive powers, so I’m not the one in charge of managing the crisis and implementing the measures. I do think, however, that in the case of successful female leaders who do wield executive powers and have been able to manage the pandemic well and even managed to increase the public’s confidence in them, it was a combination of the ability to manage the crisis and put people’s health and lives above their own ambition to show their remarkable abilities. And, at the same time, the second thing I consider crucial for managing the pandemic successfully is communication. Society was and continues to be under a lot of pressure. Thousands of people are dying. Many people are losing their loved ones. We have been fearing for our lives. In other words, the most essential, fundamental things, including the loss jobs and social security. Such an atmosphere in society also demands communication that is empathetic and sensitive. Some men were not capable of this, unfortunately, and I feel that in more countries women fared better in the test than men.

ES: And then there are those among us who perceived the whole crisis as a threat to their personal freedom. Which is something that we, in post-communist and post-totalitarian countries, are even more sensitive about. In your opinion, Madam President, how well do you think public representatives have been communicating the measures and restrictions to the public?

ZČ: First of all, I do not have the illusion that you can get through to all people, regardless of how well you manage to communicate the message. There’s a percentage of people who want to hold on to their beliefs and their interpretation of the world. And no matter how hard you try to communicate the message, they won’t listen. This of course doesn’t apply to the whole population, but there was a large majority of people who needed to hold on to some certainties and needed to know why curtailment of freedom was necessary and to have a rough idea what was going to be happening. Therefore, clarity and conciseness needed to be combined with empathy. That’s how I believe it’s possible to get the majority of the population on board, even those who are flirting with the idea that restricting personal freedom is a line that cannot be crossed, which isn’t true. The boundaries of my personal freedom only extend as far as yours.

ES: Mrs. Albright, it’s impossible for me not to ask you about Václav Havel. Do you ever think about how close you were and how he influenced you as a politician, as a woman?

MA: Thank you for this question. I came to America with my family in 1948. People wanted to know what country we in fact came from. They did have a bit of an idea of what was happening during the Cold War. And that not much had been going on in Czechoslovakia. That’s until 1968. The Poles and Hungarians were more active. And people kept asking us why no one in our country was doing very much. Normalization was horrible, but everything suddenly changed after 1989. Americans knew what was happening and they knew who Václav Havel was and where Czechoslovakia was. They were following the events on Wenceslas Square and at Prague Castle. I didn’t know Václav Havel personally at the time. And then I returned to Czechoslovakia in 1990. I spoke with Jiří Dienstbier, who was the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and he asked me if I’d like to go to the Castle and meet Václav Havel. Of course, I did. And I asked him what we in the USA could do to help. It was January and it was snowing, and as I was crossing Charles Bridge I was thinking about how I understood the people here and that perhaps I had never really left. I know I had to help. Later, Václav Havel came to American and appeared in Congress. And everyone knew what a moral and wonderful president he was. During those years I was very proud to have been born in Prague and that I could talk about this person. Then we became truly good friends. Who would have thought that Marie Jana Korbelová could be a friend to such a truly wonderful person who understood what love is.

ES: Do you think kindness is higher on the list of traits that make a good leader than, say, the desire to be a strong leader, lead a team or even a whole country?

MA: I think he never really wanted to be a leader. He didn’t think of himself as a leader. But he was a good leader because he wasn’t interested in power. He was a leader because he didn’t think just about himself. In America, he lived near me, just a few houses down. We saw each other often, and it was wonderful to see him be so humble. And that humbleness made him a great leader.

ES: Madame President, now for a slightly provocative question, and I don’t envy you having to answer it. Do you feel you’re in some ways similar to Václav Havel?

ZČ: (laughter) I certainly don’t dare to characterize myself that way. Of course, there’s so much about him that’s inspiring: I remember when I was still a little girl and he was a dissident, and how my mother, who was a big fan, kept pointing him out to me. Of course, I remember the transformation during the revolution when a dissident suddenly became president. It was something amazing. I consider him to be a person who put values in politics, and his importance and story were too big to stay within the confines of Czechoslovakia. Even today he is seen as our president, even though the country separated, and as a person who was one of the few in politics with values. I bow to him and would certainly not compare myself to him in any way.

ES: Going back to Mrs. Albright’s thesis that Václav Havel didn’t really care about power, is that something you have in common? (Or is the approach and thinking about politics inevitably so different thirty years on that the inner motives of public officials are no longer comparable?)

ZČ: I think it’s the same for me. In terms of the motivations that led me to the decision to candidate and even in terms of how I perceive the office. I’ve said it often: it’s a public service. That’s what it means to me.

ES: If I may, I’d be interested to hear how both of you remember the key moments of our shared and relatively recent history. Let’s start with 17 November 1989. Do you recall where you were, what you were doing and what was running through your minds? What were you hoping for and what did you believe?

ZČ: I remember that time well. I was 16 I think, in high school. The time just before I began paying attention to political discussions here at home was actually a snapshot of the schizophrenia we were living in, because different discussions were taking place at home, and these were different than the official rhetoric outside, in schools, on television and so on. And then came the moment when the dimorphism could finally collapse. I also remember the time in the streets. The crime rate suddenly dropped; there was a feeling of solidarity. I used to go to the square here in Bratislava, and the atmosphere was wonderful. It was filled with hope. We were saying we’d catch up to Austria within three years. It was a time of great expectations and high hopes. What followed of course were great trials and tribulations, and the process of learning what democracy is, but I remember that time as a very positive moment in our history that brought many opportunities, including those that, for example, led me to study law.

MA: I was at Georgetown University at the time. In the Eighties, I travelled often to Communist countries. I studied what was going on in Central and Eastern Europe. When I travelled to Prague, I would meet with various people and journalists. I used to stroll through an empty Wenceslas Square. When the Revolution came, I was there in spirit. Because I knew where everything was taking place, and I was thinking about the students who were behind all the events. I was contemplating what was going to happen, and if it would all go sour again. But it was optimistic. I was Jiří Dienstbier’s close acquaintance at the time because he was in America when I was writing my dissertation about Prague Spring 68. We often spoke to each other. And suddenly he was the Minister of Foreign Affairs. I called and asked him what I could do to help. And he said: something for the students. They’re the ones who got the ball rolling. It was a kind of joining of the people I knew. When I then came to Prague, strolling through Wenceslas Square and thinking about what happened on that balcony, about the people with the keys and everything around that, was fantastic. I was thinking that this was the country my parents used to talk about. That it’s a special country. And what had come should have.

ES: And the country in this form lasted until 1 January 1993. Was this the moment that the euphoria began to diminish? Or were you not sad about Czechoslovakia splitting apart?

MA: I wasn’t sad. I once asked by parents if I was Czech or Slovak. And they said Czechoslovak. And that’s how I thought of myself. But I understood what happened. And that it was important. If you look at how the two countries used to work together, you can see it’s much better now. I’d also like to say, and this will interest Madame President, that my father was the Czechoslovak ambassador to Yugoslavia, and my first diplomatic mission was being the little girl who welcomed delegations at the airport. I wore a folk costume. A Slovak folk costume, from Piešťany. Now you can see it in the Czech and Slovak National Museum in Iowa. I hope you’re proud to be the president of Slovakia.

ES: Or we can expand on that, Madam President, and ask if you wouldn’t rather be the President of Czechoslovakia?

ZČ: (laughter) I do not pose questions to myself that are unrealistic. I’m sorry, but that’s my answer. But regarding the moment of separation, I do remember it, of course. Here it was linked to the period of “Mečiarism”, which is a darker moment of our modern history. At the time I was not a fan of the fact that the country I felt I was a citizen of was splitting apart. With time, I can, however, say that relations between Slovakia and Czechia and between our nations are better, more positive and less fraught. Development is more authentic and correspond to what people here want, including whether it’s a success or failure. So, in the end I think that the state of things as they are is, in terms of quality of relations, good. At the same time, I’d like to say I like the fact that we, or the historical milestones linked to us, are associated with the word “velvet”. Because just as the revolution in the Eighties was peaceful, civil and amicable – which is why it received the moniker “Velvet” – our divorce or separation was as well. Other important milestones in the development of the Slovak Republic – for example, the mass protests from three years ago in response to the death of journalist Janek Kuciak and his fiancée – were more or less the same: the government was replaced, but in a very civilized and peaceful way. We can say that important changes in modern history took place in our two countries in peaceful, polite and “velvety” way, which is not always the case even in long-standing democracies.

MD: Another milestone was the accession of the Czech and Slovak Republics to the European Union in 2004. How fundamental was this step?

MA: I believe membership in the EU was and is really important. I grew up in a different time, when Europe was divided, and it was a tragedy. We have to do everything we can to keep Europe united. As an American, I can say that it’s very important for us to work together. There are very complicated problems that demand such cooperation. We think about democracy in the same way; we want our people to have a good life. It’s important, and I’m very happy that you joined the European Union. When Czechoslovakia split apart it wasn’t easy. And not only is membership in the European Union important, but so is membership in NATO.

ZČ: It’s of course essential and very important for us. We became part of a society we had historically essentially always belonged to culturally and in terms of values. I’m happy to be a part of it. Whether it’s important from the perspective of human rights – when I used to represent people as a lawyer, I would use the European legal framework or European institutions to defend individual rights – or from the perspective of the benefits stemming from possible national cooperation, information exchange, or even the financial flows that function under European cooperation. As Mrs. Albright also said, what’s important is the vision and future of the European Union. We know that discussions are soon set to start on the future of Europe, on what shape European institutions should take going forward, what gradual development there should be in them. What I consider important is the unity of the European Union. Despite the diversity that each country naturally represents.

ES: And finally, the date 15 June 2019. Mrs. Albright, do you know what happened that day?

MA: I can’t recall right now.

ES: The first female president of Slovakia was inaugurated and took office. I’m interested how you felt about it.

MA: I may not have remembered the date, but I do remember feeling elated. First because it is a country I know, but also because it was a woman who understands politics, is smart, and wants to do what’s truly important – for her people, for all countries, in the neighborhood and the world over. I think that’s important, not only for Slovakia, but also for the whole of Europe. Slovaks must be delighted to have such a good and smart president. I’m looking forward to meeting you in person. I’m sad I don’t speak Czech as well as I did when I was a girl, but I’m happy that we could do this interview together.

ES: How do you remember this day, Madam President? Do you have time to reminisce?

ZČ: (laughter) You’re right – I don’t. Life passes by quicky. The less than two years I’ve been in office feel more like ten years in terms of the number and variety of events. That day was of course very high profile. It was a big event. Everyone told me to enjoy it, but I don’t think I really did because I felt I had to set off on the right foot and do well all the things that were new to me at the time. But it’s a milestone in every sense of the word that changed by professional and personal life fundamentally. And not only mine, but to a degree my friends’ and families’ as well.

MD: One last question in conclusion. The global pandemic has the potential to overshadow the other problems we are facing. What issues should we not let slip past us even in the middle of a crisis?

MA: We should think about the things that are threating democracy. What’s happening, who’s jeopardizing it. We should think about what Russia is doing. And what it does not want us to know. People have to truly understand the information they’re getting, what’s happening and why it’s happening. Influences and cyber-instruments that are a threat to democracy make me nervous.

ZČ: As you said, other than the pandemic, we have to focus on all weaknesses that this emergency has highlighted and revealed – especially social inequality, poverty, the deficit in health care – but also issues like domestic violence, which has shown to be a very big problem during this crisis. There are of course topics that I’ve mentioned, such as climate change. We often say that we are possibly the last generation that can still do something to reverse the unfavorable trend. Another major topic is the responsibility of social platforms, especially in the context of hate speech and fake news. This is very closely tied to another phenomenon that is endangering democracy the world over: the inclination to elect populists.

Aktuální číslo + Vogue Leaders 06/21

149 Kč / 5.99 €

První vydání Vogue Leaders vychází společně s červnovým číslem Vogue CS za cenu 149 Kč.

Koupit:

Zuzana Čaputová became the first female president of the Slovak Republic on 15 June 2019 and the youngest person ever to hold this office. Previously, she was a lawyer and civil activist. She had long worked with Via Iuris, an association that focuses on strengthening the rule of law. She has also been active in environmental issues. For her efforts to close the toxic landfill in Pezinok she received the Goldman Environmental Prize. In 2019, she was awarded the European Personality of the Year, an honor bestowed in Brussels for extraordinary successes in politics, business and innovation.

Madeleine Albright was the first woman to become United States Secretary of State, a position she held from 1997 to 2001. Prior to that she was US Ambassador to the United Nations. She played a key role in expanding NATO to include former Eastern Bloc countries. In 2012, Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She has Czech roots. After 1989, she helped form the nascent Czechoslovak democracy and became a close personal friend of Václav Havel. She is the author of several successful books.

Emma Smetana is a journalist, moderator, musician, actor and graduate in political science. She studied European Affairs and International Relations at Sciences Po Paris and at Freie Universitat Berlin. She started anchoring the Television News at TV Nova in 2012. Four years later she joined the news team at the online channel DVTV. On April 12, a day before the interview, she gave birth to her second daughter, Ariel Ava.

Michaela Dombrovská is an assistant professor at Silesian University in Opava where she researches different types of literacies and public policies. She has been active in journalism for more than ten years. She is the author and co-author of several scientific and popular books. Her latest book entitled Informační detox (Information Detox) was published this year by Grada. She has been working with Vouge CS since 2018.

Vogue

Doporučuje

Rozhovory

Co je dnes láska? A existuje ta opravdová? Ptali jsme se těch, kteří nás inspirují

Natálie Debnárová14. 2. 2026

Vogue Leaders

Nehera. Odkaz československé oděvní historie jako pilíř globálního úspěchu

Jana Patočková13. 2. 2026

Vogue Leaders