Vogue CS in English

Notes On Godard and Growing Up

Donari Braxton8. 11. 2022

University of Paris, somewhere in 2001. My first Film Theory 101 class. The Israeli film critic we’d been assigned is excoriating Jean Luc Godard with the kind of clinical disdain that all Jews, myself included, instantly recognize as laced with j’accuse. Godard’s characters were “cookie-dough billboards” for vapid Marxian agitprop, his philosophy “sophomoric,” his cinematic vocabulary the pagan incarnation of a “slow Ping-Pong match” that “goes nowhere and ends nowhere.”

The last part stuck with me. A Ping-Pong volley never-ending, never-going. I raised my hand to ask the professor:

“What’s wrong with that?!”

“Everything,” he said, along with a sort of gentle chuckle.

I didn’t find his answer funny at all though — I was serious. I slouched back into my chair feeling dumb and American, both of which I was.

But I’ve noticed since then there’s a trend, if not an unspoken rite of passage playing out in our time amongst filmmakers and film-lovers alike. Love Godard in your twenties, or you have no heart. Meh Godard in your forties, or you have no brain. The New Wave, as zeitgeist sometimes seems to imply it, is a young man’s game.

What is a Ping-Pong volley that never rallies, never ends?

At the time, I would have answered grandiose in the spirit of Cahiers. It’s a love-letter to monotony, no crescendos, no climaxes. It’s Paolo and Francesca in the Inferno’s second circle, edging for eternity –– that’s sexy. It’s an art of equal emphasis.

And what’s wrong with that.

Godard movies don’t go, and don’t end. They swing back and forth like pendulums in a narrow. Generally speaking, nothing happens. I can’t remember what Masculine-Feminine (1966) is about while I’m watching Masculine-Feminine (2022). I think that his 1962 film, My Life to Live, is about a prostitute, but mostly I remember it as a militant twelve-part sociological tract about class struggle complete with statistics and Brecht-worship. Sometimes, like in Band of Outsiders (1964), Godard narrates his own movies and simply explains to you what’s happening. Still, nothing happens — and how chic.

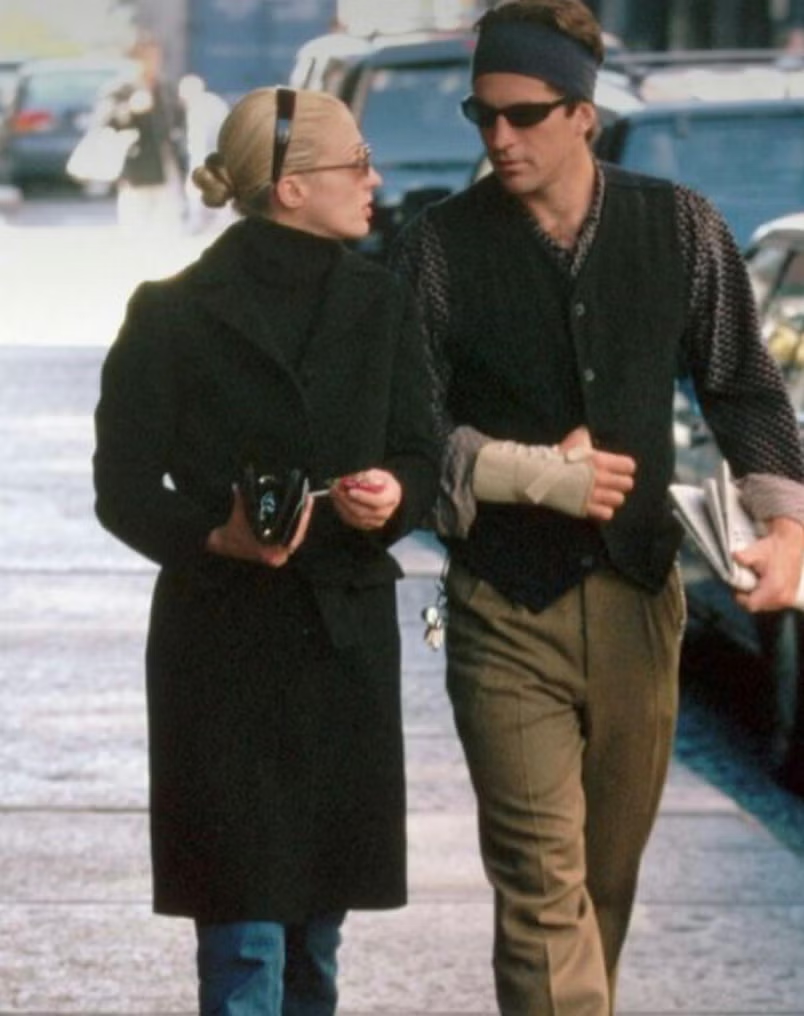

Then, there was the way that a Godard film looked. You think of actors backlit with stylized light flare, or of zoom lenses pointing street-level though the glass façades of Paris cafés for interior shots — breakthroughs at the time that to this day feels bohemian. Even the custom title-card typeface, as if excised with Exacto knives, screamed of the Avant-Garde.

You’re 18 years old. You take yourself seriously. You eat that shit up.

But what happens? I don’t know. Time does, I guess. You fall ass-backwards into Easy Rider and the New Hollywood 70’s. You want a laugh, you watch Instagram reels. You learn that both Helvetica and Futura fonts are free to use on your Apple computer. The world changes and you get older — I did.

And for some of us in the TikTok era, that eternal Pong called Godard grows harder to stomach. Visually, you’ve grown weary of the supernatural fourth-wall breaks — just tell the damn story, Jean. And audibly, the dronings-on of his characters — all of whom mouthpiece-tools for Godard’s worldview, politics, favorite literary references — sound more like the hollow jaw-jangling of ventriloquist dummies.

Suddenly you’re forty and cynical, and what’s wrong is “everything” is wrong. You no longer have the same appetite for the conceit of big ideas.

For me, it took a public health crisis for Godard and I to make up. I’d just moved from my lifelong home of New York to Los Angeles when Coronavirus hit. Like everyone, I spent months slaving over social media and YouTube. I laughed at my own jokes and took masked walks through a world that looked the same but that was unrecognizable.

More than once through the pandemic, Godard’s film Alphaville rushed to mind. It’s a prescient 1965 sci-fi parable about the alienating effects of technology. Which, he was right about that. But more importantly, Godard shot Alphaville in Paris without special effects, futurist wardrobe or even any special set design. Instead, to set the tone for the film’s dystopian future, he simply leaned into oblique, single-character framing, into kinetic pacing and disaffected dialogue. In short, he let the ideas do the talking, and seemingly out of thin air, created a completely isolating neo-noir world using perspective alone. The movie seems in hindsight to fully capture the CoVid experience, if fifty years too soon. And the point of reference felt comforting to me.

I didn’t bother rewatching Alphaville at the time. Too boring. But I did recently, after learning of Godard’s death in September, sit down to revisit his first feature film, Breathless (1960), a beatnik parable about a gangster in love. In my favorite part of the movie, we watch Jean-Paul Belmondo’s character driving his American girlfriend in a stolen convertible through Paris. The scene’s elliptical jump-cuts pair with voice-over as Belmondo pathetically laments:

“Alas, Alas, Alas! I love a girl who has a very pretty neck, very pretty breasts, a very pretty voice, very pretty wrists, a very pretty forehead, very pretty knees... but who is a coward.”

But it’s Belmondo’s character who’s the coward — a wannabe Bogart terrified of being abandoned. What struck me was how differently the scene landed now, compared to when I watched it as a kid. It all seemed so poetic, so serious back then — where now, the same character seemed so adorably boyish and fragile that I cracked up laughing out loud. Maybe isolation and the fear of loneliness hit different these days. That, and maybe it’s just easier to grapple with big ideas, at any age, when you let yourself gently chuckle at them.

I shared the full scene same-day on my Instagram Stories. A few people “hearted” it — mostly younger friends. That’s a good sign, I figured.

Vogue

Doporučuje

Filmy

Kdo je Odessa A’zion? Nová módní a filmová hvězda, kterou musíte znát

Cindy Kerberová18. 2. 2026

Doplňky

Oblíbený doplněk Kate Moss a Paris Hilton z nultých let je zpět

Anežka Lišková18. 2. 2026

Trendy