Vogue CS in English

Interview with Ami Doshi Shah of Ami Doshi Shah

Ooooota Adepo1. 8. 2020

Foto: Rhys Frampton

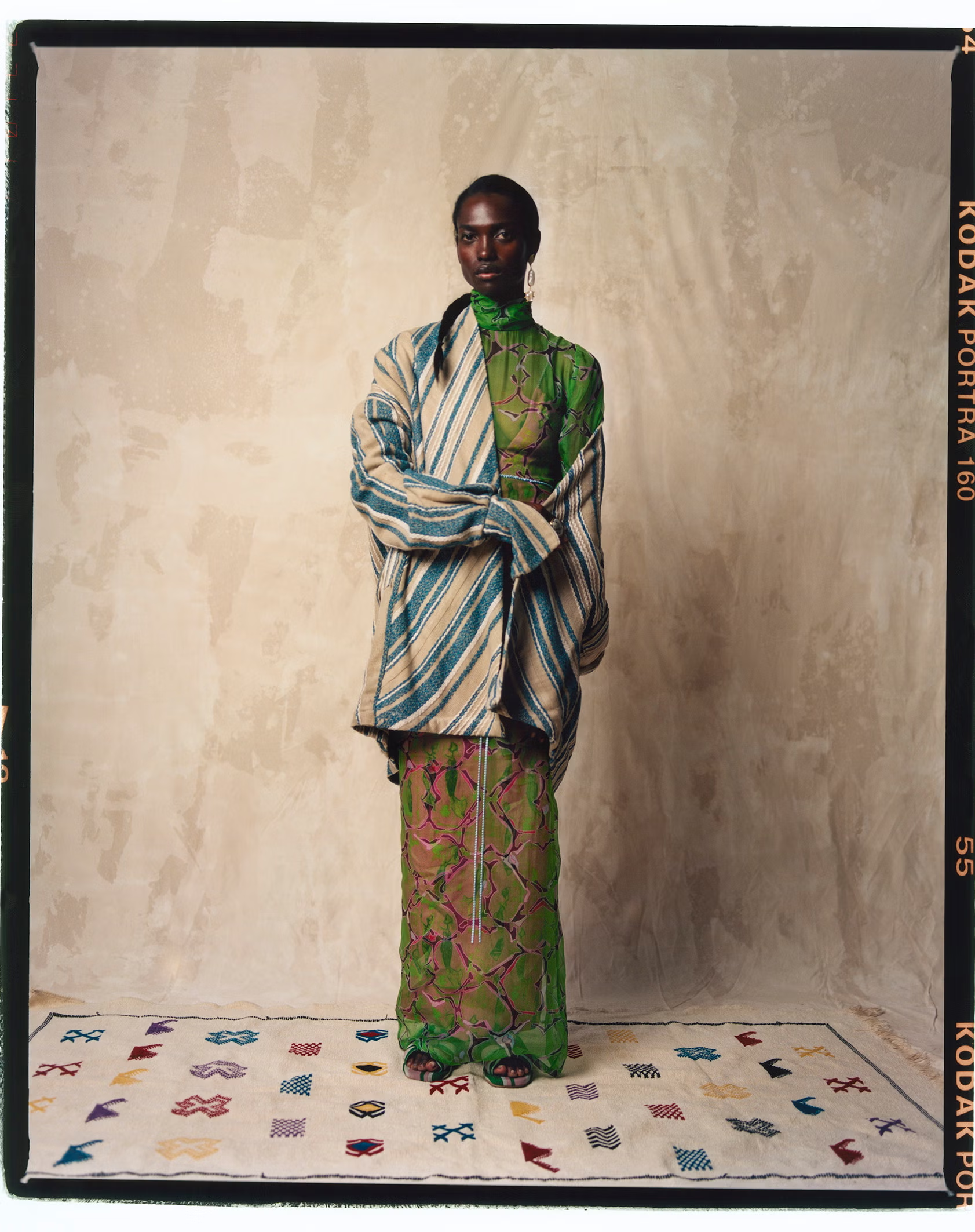

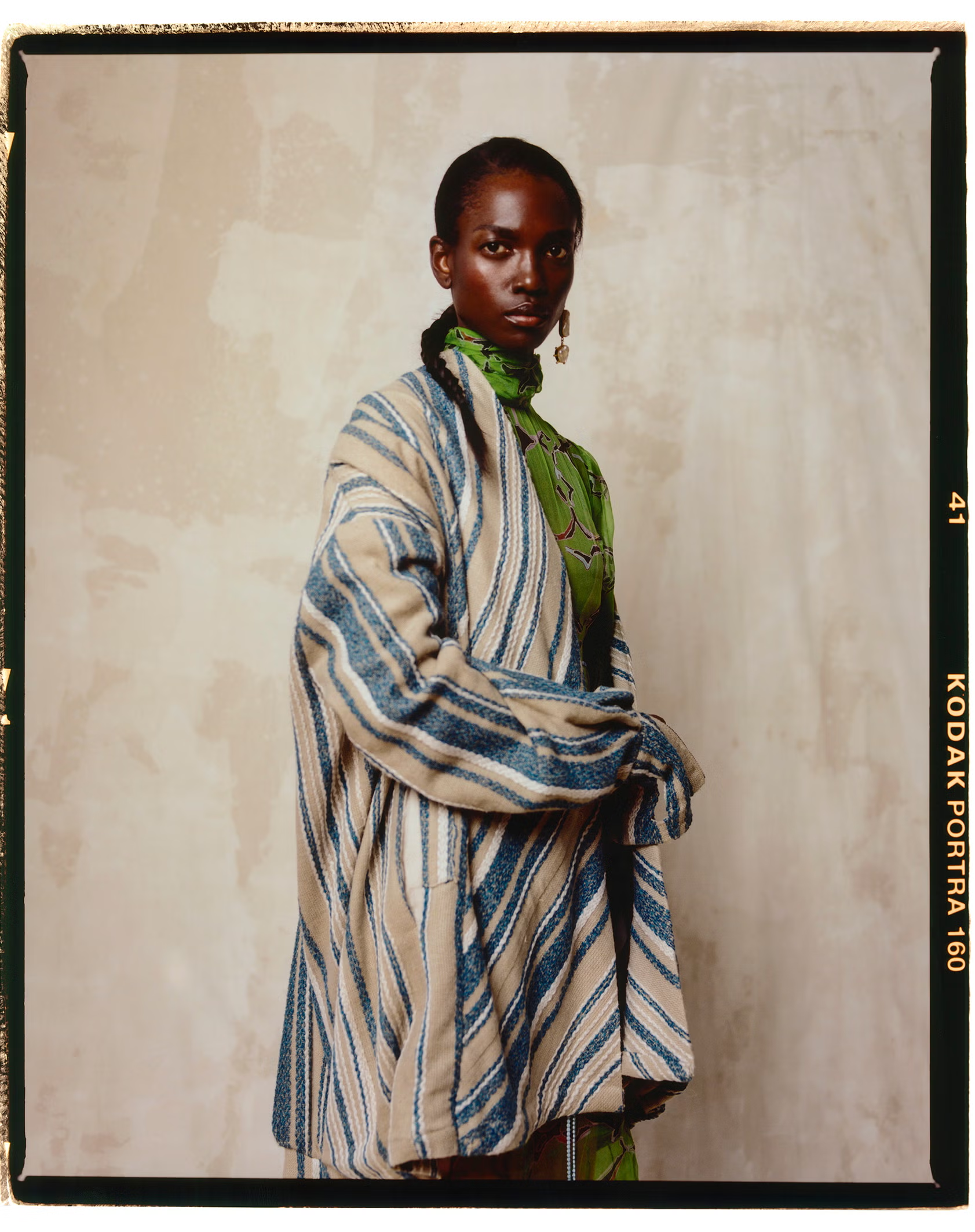

Blazer vest, shorts, Loza Maleombho (sold at Koibird); tights, Wolford; boots, Michael Kors; necklace, Ami Doshi Shah (sold at Koibird).

Ooooota: Through your Salt of the Earth collection, please discuss how you investigate the concepts of power and submission.

Ami: Salt of the Earth was one of a number of conceptual projects I’ve partaken in since I began my design practice. The first point of research was the phrase, “Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men.” Matthew 5:13, King James Bible 1611

It has now come to be used as a colloquial idiom referring to the fundamental and basic goodness in a person, verging on naïve.

I started doing further research and discovered that medieval conquerors used to ‘salt the earth’ of conquered lands and people to render it infertile and used this mineral as a form of poison. I became fascinated by the fact that one mineral can express itself with duality and began researching how I could translate those metaphorical and symbolic characteristics in the properties of salt into a story of Kenya’s neo-colonial legacy. It’s essentially natural to life with conversely destructive properties. Power and Submission. After all, colonial rule re-organised local life, affecting access to land, resources, property, authority structures and had huge cultural ramifications including dress. Dress and adornment have always been a tool for individual self-expression and social identity but also a tool for subjugation and conformity. The bodies adorned with animal skins, feathers, beads became a source of derision despite the innate connection to nature and the spiritual symbolism to status and rites of passage.

Post-colonial times meant we were and are constantly under the Western gaze. Internally, pursuing equality and personal freedoms that democracy dictates yet still playing to western perception and stereotypes to some level.

The aim of the installation presentation of this work at Somerset House last year was to create an immersive space where the pieces express salt’s ability to poison, erode and decay using the process of patina and conversely the material’s ability to create, rejuvenate and give life – the literal and physical manifestation – crystallisation. The story of a fraught legacy and our own ability to rise above, resist and ultimately triumph.

AMI DOSHI SHAH

Ooooota: As a Kenyan native, you use locally sourced materials and remnants of the mining industry as your raw materials. Why is it important to create from Kenya’s portion of Earth?

Ami: One of the remits for when I started my design practice was to work with materials that were locally available be it brass or leather or locally sourced minerals. My work tends to be an experimentation of scale, form and texture and I wanted to use materials that are not innately precious and engineer them in unexpected ways. I wanted to work with them with a sense of preciousness. Even when I use minerals, I love using uncut, raw stones or faceting them in irregular ways. I suppose that it’s important to create from Kenya’s portion of Earth because it’s my way of expressing the incredible human and natural beauty that Kenya represents.

Ooooota: Some of your adornments are bold with heavy tribal motifs, while some of your jewellery feels modern and contemporary. Why is it important to show that African design, particularly in jewellery can have the same lines, finesse and at times minimalism that we encounter with other modern designers, in addition to being assertive?

Ami: I think I mentioned before that there is a huge misnomer of what constitutes African design. We are a continent of 54 Countries, each with our own national identity. I am a Kenyan with South Indian heritage and a European education. What I create is a product of thousands of visual, human and cultural experiences and with the globalised world we live in, this is magnified even more so. I am drawn to simple and clean forms with an element of whimsy, scale and texture. Each designer on the continent is carving out their own aesthetic and collectively, we exhibit the plethora of style, craftsmanship, colour and personalities that constitute African design.

Ooooota: Do you produce entirely in Kenya? If so, how do you ensure your team is adequately trained to uphold the standard of quality expected in today’s jewellery market?

Ami: Yes, I produce entirely in Kenya and up until last year, the majority of what I made and sold, was made by me in my studio. I have now started working with a very accomplished maker and metalsmith to produce collections since Salt. We have a wonderful level of trust and understanding in the interpretation and making of the master samples, which has been invaluable, personally and to the brand.

Ooooota: Would you like to see more collaboration and connectivity amongst African designers on the continent or in the diaspora? If so, why?

Ami: Absolutely, I would love more collaboration and connectivity amongst African designers. During the IFS programme (of which Salt of the Earth was the culmination) run by the British Council, British Fashion Council and the London College of Fashion, I had the opportunity to build friendships and communities with 16 other designers from around the world. Two of them, Cedric Mizero and Thebe Magugu were from the continent. Both are incredible designers and human beings whom I hugely respect. But had it not been for IFS or people like Sunny Dolat (Nest Collective), Omoyemi Akerele of Lagos Fashion Week, Style House Files and organisations like SheTrades, I feel like my world would be a much smaller place.

Ooooota: Your collections seem to encourage a reverence towards the Earth’s raw materials and precious/semi-precious stones. Do you see human beings as having a responsibility over the mindful use of these resources?

Ami: I do. I actively choose not to use precious stones in my work but for me the important thing is to make objects in very limited production runs and to recycle or up-cycle as much as possible. I think that hopefully COVID-19 has taught us to be more considerate of what and why we choose to have the things that we do. Whether that’s a piece of jewellery or relationships. They have to bring you some joy.

Ooooota: What does beauty mean to you?

Ami: I’m going to use a quote by author Alan Moore where he says:

“Beautiful things are prepared with love. The act of creating something of beauty is a way of bringing good into the world. Infused with optimism, it says simply: Life is worthwhile.”

Ooooota: How can jewellery be used to embellish, enhance, and/or tell a story?

Ami: The home or context of jewellery is the human body, the most poignant storyteller of all. Jewellery or adornment is our way of telling the world this is who I am, what I stand for or simply…my identity. Away from the body, a piece of jewellery is simply a static object.

Ooooota: Where do you derive inspiration?

Ami: Architecture, books on Art history or anthropology, the news, a conversation, a postcard, a landscape and sometimes, simply the material itself. The point of inspiration is honestly limitless, but I have an instinctual draw to a certain aesthetic.

Ooooota: How important is it for African designers to collaborate with each other and/or with the rest of the world? Is the former type of collaboration of greater value than the latter?

Ami: It is very important as that is how we can continue to dispel the preconceptions of what is African Fashion/ Art/ Design. Cross-pollination and creative collaborations are important regardless of where they come from and who they are with as long as there are synergies in approach and thought process.

Ooooota: How do you see the Ami Doshi Shah brand evolving?

Ami: I’d like the brand to remain small but would like to extend into other areas of product design. I really have huge gratitude for being able to do what I do and seeing the brand growing organically.